A movement toward making

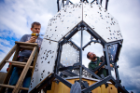

First-year architecture students install their studio projects, 'Ritual Space,' at Artpark in Lewiston, NY, in the spring of 2018. The design-build focus of UB's freshman architecture studio dates back to 1982, when faculty member Don Glickman initiated a simple but provocative exercise using cardboard boxes. Photo by Meredith Forrest Kulwicki

by Bradshaw Hovey

Published November 22, 2019 This content is archived.

A movement that came to be known as the School of Architecture and Planning's “maker culture” emerged in the 1990s. It expressed an interest in hands-on work, a desire to build at full-scale, a curiosity to explore the properties of building materials, an inclination to experiment and, most of all, a drive to experience the materiality of architecture in an unmediated way.

The most celebrated events in the evolution of maker culture at UB included a number of provocative projects around the turn of the millennium led by architecture faculty members Mehrdad Hadighi (who also served as program chair) and Frank Fantauzzi, and inspired by collaborators such as Clarkson Chair Daniel Hoffman and McHale Fellow James Cathcart.

Working without a script

A 1999 project entitled “Slice” cut a large and long section from the wall at the rear of the James Dyett Gallery in pre-restoration Hayes Hall, rotating it on an axis to reveal the building's then-vacant fourth floor. Photo courtesy of Frank Fantauzzi

At the Big Orbit Gallery they created an installation made of 4,600 wooden shipping pallets, one element being a large ovoid form, the second a void in the same shape. A not-to-code project entitled “Slice” cut a large and long section from the wall at the rear of the James Dyett Gallery and rotated it on an axis to reveal the vacant fourth floor of Hayes Hall behind.

In 2001, UB clinical assistant professor of architecture Bradley Wales initiated the Small Built Works program, which continues today and has produced conceptual design-build projects throughout Buffalo ranging from a pocket park to bus shelters to affordable housing prototypes.

But the most notorious projects was The Putnam House. In 2007, Fantauzzi and Wales devised a studio project that was to involve finding creative ways to dismantle one of Buffalo’s typical two-and-a-half story two-family wood frame houses. This would be an unmediated encounter with the materiality of (un)building, to be sure.

The Putnam House with rotating front facade. Photo courtesy of Frank Fantauzzi

The Putnum House today. Photo by Maryanne Schultz

Only part way through the project they decided they should find a way to save the structure instead. This would involve a radical opening up of spaces inside that might serve as a prototype for modernizing an important category of housing in Buffalo. More sensationally, it included cutting the front façade away from the building and rotating it on a huge axle the students engineered.

Not everyone was impressed. Some of the neighbors complained. Building inspectors objected to work done without permits. But Fantauzzi maintained the project made an important point. It was a challenge to the whole city, he recalled recently. “By questioning that symbol, the stability of the façade, we are in essence questioning everybody’s relationship to the house and to the family.”

Prior to its move to Hayes Hall in 1977, the School of Architecture and Environmental Design was in Bethune Hall, aka the Buffalo Meter Building on Main Street. Here students were given the task of designing their “proximate environment” anew each year, manipulating and reconfiguring furnishings into their learning space. Image from NOTES, Newsletter of the School of Architecture and Environmental Design, May 1973.

The roots of maker culture

But it would be a mistake to imagine that maker culture at UB erupted spontaneously in the 1990s. Faculty and students had taken a hands-on approach to design from the earliest days of the school, redesigning the space in Bethune Hall, the school’s original home, on an annual basis, and fabricating furniture out of hollow core doors.

The program’s early focus on Building Systems Design had much to do about how things go together. Professors like Gunter Schmitz and visitors like Konrad Wachsmann promoted the dream that better systems could mean more affordable buildings. Buckminster Fuller, a frequent visitor, lectured about geodesic domes and other big ideas. Walter Bird, an adjunct faculty member, taught fabric structures.

In 1982, Don Glickman, who had worked for Harold Cohen at Southern Illinois University, dubbed by some as the “Second American Bauhaus,” was hired to chair the twice-born Department of Design Studies. (Its earlier incarnation had been led by Peter Reyner Banham). Glickman brought to Buffalo a simple but provocative freshman year studio exercise.

The Living Wall project was developed and produced in 2010 by first-year architecture students under the direction of architecture faculty members Shadi Nazarian, Christopher Romano, and Nicholas Bruscia. The students were asked to design and construct a minimal dwelling unit with an entrance, internal circulation and sleeping areas for a minimum of three people out of 2”x 4” lumber and CDX plywood, a standard material in residential construction.

Each student was tasked to design and build a shelter using just two 4’ x 8’ sheets of treated corrugated cardboard, which they would carry one mile into the woods at Letchworth State Park and occupy for 24 hours in whatever weather October brought them – sun, rain, cold, even snow. It was a powerful experience of the gestalt of building.

Versions of the freshman design build experience conducted two decades later were conceptually similar but materially and operationally more ambitious, one year building a “Living Wall” of small shelters for a year-long installation at the Griffis Sculpture Park in Chautauqua County, another creating sculptural “Reflection Space(s)” at Silo City along the Buffalo River waterfront, a third at Art Park under the rubric of “Ritual Space.”

Elevator B, a 22-foot-tall tower and habitat for bees, has its origins in a student design competition and collaboration with Buffalo-based materials manufacturer Rigidized Metals. Photo courtesy of Elevator B design team

Marrying technology and craft

In recent years, other members of the faculty have taken a slightly more practical turn, forming partnerships with local industrial companies to explore and expand the potential of basic architectural materials.

Gaining widespread attention is the school's longstanding experimental research with Rigidized Metals on the structural and design possibilities of thin-gauge sheet metal. An internationally award-winning student project, “Elevator B,” a 22-foot-tall steel tower to house a hive of honey bees, emerged out of a design competition sponsored by Rigidized Metals and organized by the Ecological Practices Graduate Research Group. Assistant professors of architecture Christopher Romano and Nicholas Bruscia carried the research forward with Project 2XmT, a self-structural assembly of folded metal, installed at Silo City in Buffalo. A current collaboration with Rigidized, led by associate professors Laura Garofalo and Joyce Hwang and assistant professor Nick Rajkovich, will support two student design-build projects in ecological design for the post-industrial landscape of Silo City.

For nearly a decade Omar Khan has led a collaboration with Boston Valley Terra Cotta to connect age-old craft with digital technology to push the limits of design and fabrication. The collaboration has evolved into the Architectural Ceramic Assemblies Workshop, which engages architects and engineers from around the world, along with UB architecture faculty and students, in the development of terra cotta facade prototypes.

In 2015, UB placed second in the international Solar Decathlon with the GRoW Home, a net-positive energy solar dwelling designed and built by students and now installed behind Hayes Hall. The design-build effort, led by Martha Bohm, associate professor of architecture, and Kenneth Mackay, clinical associate professor of architecture, involved hundreds of students across UB. Over the past few years, associate professor Georg Rafailidis and Stephanie Davidson have initiated a line of inquiry into the structural potential of paper casting as an investigation into temporality and biodegradabilty in architecture.

Dennis Maher, a clinical assistant professor who explores the creation of built environments through assemblages of urban artifacts, is taking the art of making to the community through his nonprofit organization, Assembly House 150. Operating out of a former church in downtown Buffalo, AH150 serves as a community space, and often the setting for Maher's studios, for explorations in the construction arts.

Among a series of projects led by UB architecture faculty member Brad Wales' Small Built Works program is Front Yard, an installation of three towers each composed of 42 steel panels. The towers project a stream of environmentally responsive audio and video onto the facade of the Burchfield Penney Art Center (BPAC) in Buffalo. Photo courtesy of BPAC, by Bill Wippert.

Professor Jean LaMarche pinpointed the significance of the “maker culture” movement in an introduction to a photo essay in the school journal Intersight about display systems that students designed and built for a visit by an accreditation team in 2003 (they were impressed). Increasingly, LaMarche wrote, architecture education in Buffalo reflected “a fundamental concern for the embodiment of architectural knowledge.”

His emphasis on embodiment – on the body – was not figurative. By confronting the materials, tools, and processes of creation “students are exposed to the sensed conditions of direct experience and that knowledge is assimilated by the body as a form of subsidiary knowledge, i.e. as tacit, ineffable, inarticulable knowledge.”

With its beginnings as a collection of analog tools in Bethune Hall and later in the basement of Crosby Hall, the school's shop moved to Parker Hall in 2012. Today the Fabrication Workshop is the hub of the school's maker culture and one of the largest shops of any architecture school in the country.

Maker spaces

The school's shops and maker culture matured in reciprocal relation. From a small collection of analog tools, first in Bethune Hall and then in the claustrophobic basement of Hayes in 1977, the shop later moved to the airier high-bay space in Parker Hall. In 2006, the school established the ‘Fab Lab’ in the basement of Crosby Hall with a first generation of digital routers and laser cutters. And in 2012 analog and digital were reunited in Parker in what is now the Fabrication Workshop, one of the largest shops of any architecture school in the country.

Last year, the UB Sustainable Manufacturing and Advanced Robotic Technologies research community, in which the architecture program plays a lead role, opened the SMART Fabrication Factory in Parker Hall as a space for industry collaboration on research into technology, craft and material study. The space features state-of-the-art digital tools including a multi-axis water jet machine that can cut through six-inch-thick stone, an industrial platform laser cutter, and a front-loading kiln for firing ceramics.

An eight-year research partnership between UB’s architecture program and Boston Valley Terra Cotta has evolved into the Architectural Ceramic Assemblies Workshop engaging architects, engineers and ceramacists from around the world in facade design with terra cotta. Here Team SHoP Architects works on their project in UB's Fabrication Workshop (2019). Photo by Charles J. Wingfelder

Over the decades, maker culture at UB has meant a variety of things. It has been practical, experimental, artistic, craft like, high tech, and today, perhaps, less renegade than in earlier days. It has connected learning with discovery (one of the Architecture Graduate Research Groups focuses on Material Culture). But all of these have shared a fundamental conviction that there is no way students can learn crucial lessons about materials, structure, space, and form – about architecture – without experiencing them directly.