Introduction: Legacy & Time

04.03.2020 | Elizabeth Gilman, MArch, Fred Wallace Brunkow Fellow (2019 - 2020), Editor

Intersight

As the University at Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning annual publication of student work, Intersight captures the present intellectual and cultural moments of our school. Since the redevelopment of the journal's agenda through Intersight 19, discussion has become a key component to the series as a mode of celebration, evaluation, and critique.

Intersight 22

This year’s edition of Intersight builds off of the trajectory of the past three volumes by bringing together faculty and students in a series of conversations that reflect on our school’s pedagogical development and provoke critique of ideologies, both past and present. Each centers around statements made by prominent architectural and educational figures from the past, which became pivotal in shaping the fundamental ideas behind our school’s creation and evolution. The intent behind these conversations was to reflect on student perceptions of their education; to locate current ideological focuses within the school; and to engage the collective intellect and experiences cultivated within our program.

By looking at the school's ideological foundations through the lens of time, Intersight 22 has become a tool to evaluate and situate the past year of student work in the context of the School of Architecture and Planning’s history. In terms of design and education, this past year cannot, and does not, stand alone, as each project, intentionally or not, is in some way a reaction to or reflection of the school's pedagogical development. The continuous accumulation of knowledge and experience over time, by both faculty and students, allows for the strengthening, fluctuation, and refinement of the school's driving principles. Using our pedagogical context as a basis for critique and self reflection allows the School of Architecture and Planning to keep pushing boundaries and developing new educational trajectories. Intersight 22 has aimed to tap into and understand this temporality by looking at the school's history in relation to our current stance on design education and philosophy. Through the dialogue of the conversations, it became clear that the various ways of thinking that are present have become a distinct and valued part of our school's culture.

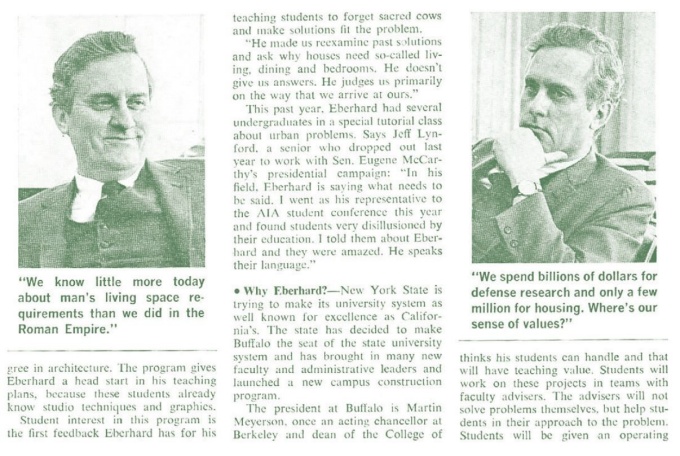

05.08.1969: This article, The Way Architect Practice Must Change, discusses Eberhard's systems approach to design and his critique of the design profession.

Foundational underpinnings

The journal opens with a response to the thoughts of John P. Eberhard, who made revolutionary strides in design education as he founded the School of Architecture and Environmental Design. The discussion was based on an interview from Engineering News-Record from May 8, 1969, entitled The Way Architects Practice Must Change. The article features Eberhard and his ideas on how to restructure architectural schools as a means to restructure architectural practice. He was much more interested in teaching students how to think than simply teaching them how to draw.

The next four conversations were prompted by statements from Buckminster Fuller, Robert M. Hutchins, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and Louis Sullivan that were used as a prelude to a master plan for the School of Architecture and Environmental Design, submitted by Dean Harold Cohen (1974-1984) to the university in 1975. The excerpts were taken from Fuller's 1963 book, Ideas and Integrities: A Spontaneous Autobiographical Disclosure; Hutchins' 1943 book, Education for Freedom; Moholy-Nagy's 1946 book, Vision in Motion; and various selections from Sullivan's writing, collected between 1895 and 1918.

Buckminster Fuller worked within and across many different fields of study, including architecture, engineering, education, and design. He was interested in using technology to solve global issues and to promote a holistic view of the planet.

Hutchins was an educational philosopher who believed strongly in secular perennialism - the idea that broader topics that are of “everlasting pertinence” should be taught in universities over specialization. He wanted students to learn how to think rather than what to think.

László Moholy-Nagy was an artist whose goal was to "illuminate the interrelatedness of life, art, and technology.” He taught at the Bauhaus School of Art from 1923 to 1928, and opened the School of Design in Chicago in 1939. Moholy-Nagy kept an account of his efforts in developing the curriculum for his school, which were posthumously published as Vision in Motion in 1946.

Louis Sullivan was an architect who attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1872 and the Ecole des Beaux - Arts in 1874. Many of Sullivan’s thoughts on architectural education seem to be a direct response to the Beaux - Arts educational model, critiquing their antiquated traditions and historicism.

These snapshots of ideas from 1895, 1943, 1946, and 1963, captured as moments of inspiration in 1975 by Dean Cohen, allowed for the school to further develop their foundation of thought. By simultaneously responding to these ideas and our current educational context, the conversations were able to flow between past and present to discuss current pedagogical themes within the school.

The culminating conversation was different from the previous five in that it didn’t have a preluding prompt derived from historical content. There was no quote or excerpt to steer the discussion. Rather, it served as a moment of projection. The conversation focused on where the school is headed, future plans, and the expansion of both pedagogy and culture.