Ciao Buffalo!

The School of Architecture and Planning shares the story of a university and its city with the world

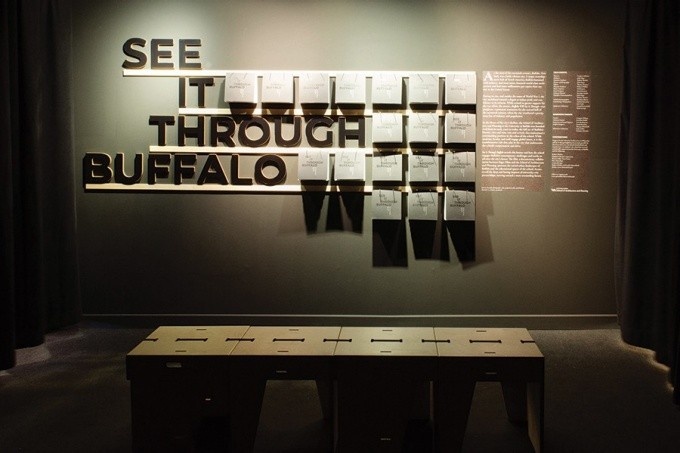

Inside the UB exhibit. A team of five students designed the catalog, the bench, and the look and feel of the space. Photo: Plane—Site

This article was originally published in the fall 2018 issue of UB's AtBuffalo alumni magazine.

By Rebecca Rudell

La Telefonata (“The Phone Call”)

ON OCT. 27, 2017, Robert Shibley, dean of the School of Architecture and Planning, along with faculty members Omar Khan, Korydon Smith and Gregory Delaney, sat in a conference room waiting for a phone call. In due time, it came, bringing wonderful news: UB was invited to participate in “Time Space Existence,” a global exhibition to be held in conjunction with the Venice Architecture Biennale. It was one of only 32 academic institutions in the world selected for this honor.

The Architecture Biennale has been held every other year since 1980, alternating with the even more widely known Venice Biennale, which began in 1895. While the latter celebrates artists, from painters to musicians, the Architecture Biennale showcases the most inventive and influential architects in the world. Both events, set in the glorious interiors of centuries-old palazzos along Venice’s canals, draw hundreds of thousands of people from around the world to witness the latest developments in art and architecture.

“Time Space Existence,” which has been held as an official Biennale Collateral Event since 2012 in Palazzo Bembo (where UB’s installation would be), Palazzo Mora and Giardini Marinaressa on the Grand Canal, presents the work of more than 100 architects, photographers, sculptors and universities. Its mission, as noted on the website of the Global Art Affairs (GAA) Foundation, a co-organizer, is “to heighten awareness about the more philosophical themes in contemporary art, Time–Space–Existence in particular, and make these subjects more accessible to a wider international audience.”

Palazzo Bembo, where the UB exhibit is housed. Photo: Didier Descouens

Il Concetto (“The Concept”)

Large architectural exhibitions typically include hundreds of intricate plans, drawings and models. During a show like the Biennale, explains Smith, professor and chair of the architecture department, a visitor might walk through hundreds of exhibition rooms. “Though the content may be quite different,” he says, “a lot of work is similar, with a lot of text. We wanted our exhibit to be more meaningful.”

To cut through the clutter, the committee decided to make a documentary short. The concept came together very quickly from there. “We knew it would be a Buffalo-based story,” says Smith, “about how the work of our faculty, staff and students informs the city and how the city informs what we do in terms of research and the educational experiences that students have.”

The movie would cut between scenes of the city and the school to cinematically convey the love story between the two. There would be no narration, to make the film accessible to everyone. As Shibley explains: “You don’t need to speak English to learn about Buffalo. The language is the film.”

Finally, in order to make it a fully immersive experience, they decided the screen would fill one entire side of the space, from floor to ceiling and wall to wall. The rest of the room would be dark and spare, again in contrast to the busy spaces of the other exhibitors. “We wanted to give people a moment of rest,” says Clinical Assistant Professor Delaney. “To take them out of Venice and into Buffalo.”

The concept came together so smoothly in part because it stems from a lived reality. The university, and in particular the School of Architecture and Planning, has long had a symbiotic relationship with the city of Buffalo. In fact, this connection is one of the reasons UB was selected to participate in “Time Space Existence” in the first place. People from the two arts organizations that oversee the exhibition (the GAA Foundation and the European Cultural Centre) saw articles in The Chronicle of Higher Education, in the periodical Design-Intelligence, and in Architect, the journal of the American Institute of Architects, which describe the school’s deep involvement with the city.

The exchange between the school of architecture and Buffalo goes back to the school’s founding in the late 1960s. Delaney mentions Reyner Banham, a British architectural critic who taught at UB from 1976 to 1980, and his fascination with Buffalo’s grain elevators. In his book “A Concrete Atlantis,” Banham asserts that the elevators inspired modern European architects like Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier.

The UB-Buffalo affiliation continued through the early ’80s, when, according to Bradshaw Hovey, senior fellow at UB’s Regional Institute, dozens of faculty, students and alumni were involved in the decades-long effort to save H.H. Richardson’s Buffalo State Hospital complex. They documented the vacant buildings, held symposiums to draw attention to the reuse potential of the campus, and worked on the actual rehabilitation and reuse of one of the buildings. Today, the Richardson-Olmsted Campus, which houses a luxury hotel and restaurant and is slated for further development, is a testament to what can be accomplished through passion and partnership.

Yet another example is the Bailey Green master plan created by Associate Professor Hiroaki Hata and his students. This project aims to revitalize a neighborhood on Buffalo’s East Side in desperate need of some TLC. The plan—a thoughtful mix of affordable housing, community gardens, green infrastructure and retail—won an international urban design award in 2016 and is currently being executed with local partners, including Harmac Medical Products (the neighborhood business that initiated the project), Habitat for Humanity, and Urban Fruits and Veggies.

“Today, there’s even more energy and enthusiasm around new ideas for the city,” says Delaney, crediting funding and tax credits from New York State for revitalization and development projects. “The school is able to engage students, not just on the model scale, but on full-scale projects that get installed in and around Buffalo.” Indeed, some of these projects are the stars of the film.

With the film concept in place, the team looked next to John Paget, an award-winning documentary filmmaker who has produced several films about Buffalo. Paget, a 2012 graduate of the School of Management’s Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership, was, says Delaney, “the obvious choice” to be the film’s producer and director of photography. The team was particularly excited by Paget’s recent time-lapse work.

Clinical Assistant Professor Gregory Delaney (left) and filmmaker John Paget in the Darwin D. Martin house.Photo: Douglas Levere

Il Film (“The Film”)

“It was hours of waiting and watching the robot do its job,” says Paget. The robot was used to shoot the film’s complex time-lapse shots: It held the camera and was programmed by Paget to pan, tilt and even focus as it slid along a set of tracks. It would stop, take an image, move an inch, take an image, and so on—sometimes on tracks that were 70 feet in length. Producing a single shot, from planning to setup to execution, could take a day to complete.

For a full month in the spring, Delaney, Paget and his crew came together to collect the images they needed to capture the soul of the school and its city. And while they wanted to emphasize all the positive work being done in Buffalo, Delaney knew they had to show that this “revitalization” is not happening for everyone. “We needed to show an honest image, that Buffalo has a complex history. It has a great legacy of architecture, but there are also neighborhoods that continue to see a lot of economic and population loss.” So they began with a list of 50 sites throughout the city that spotlight both triumphs and challenges, then whittled it down to locations with which UB has a direct relationship.

The result is a 15-minute film, titled “See It Through Buffalo” (inspired by a World War I slogan for Liberty Loan drives: “Buffalo will see it through”), that depicts more than two dozen scenes of the city, showcasing the contrasts that make Buffalo distinctive. The camera pans past decaying silos as well as shiny wind turbines; humble ethnic storefronts and the glorious terra cotta of Louis Sullivan’s Guaranty Building. The languorous rhythm of children on a swing set is juxtaposed against the frenzy of activity in architecture studio classes.

While the visual tempo alternates between slow motion and quick time lapses, the soundtrack—mostly ambient sound captured on-site, but with an original score by Canadian composer Eli Bennett—“maintains the film’s academic and intellectual tone,” says Delaney.

From “See It Through Buffalo.” The New York Central Belt Line, completed in 1882, continues to connect the few remaining industries scattered along its 15-mile route. Active Connections © John Paget

Gli Studenti (“The Students”)

At the same time “See It Through Buffalo” was being planned, shot, edited and revised, a team of five students—two graduate and three undergraduate—was developing the “framework” through which visitors would watch it.

Eric Burlingame (MS ’18, BA ’03), Kalyn Faller (BS ’18) and Nick Wheeler (BS ’19)—the fabrication team—were chosen to help design and build the environment that would house the film. Frank Kraemer (MArch ’19, BAED ’16) and Morgan Mansfield (BS ’19) composed the graphics team; their job was to develop a catalog and wall graphics to expand on the images shown in the film.

Burlingame, who has a strong background in audiovisual production, was responsible for designing the acoustics. As he explains, “We wanted to present the film in a way that would be totally engrossing and captivating, yet wouldn’t disturb other exhibitors.” With help from the other students, he sourced materials from across the U.S. and Europe, including a premium, floor-to-ceiling screen from Austria along with top-quality speakers and reverberation-reducing acoustic curtains made in America.

Students Eric Burlingame, Kalyn Faller and Nick Wheeler formed the fabrication team. Photo: Maryanne Schultz

Faller and Wheeler paired up to design and build a bench for the space. “We went through so many design iterations,” says Faller. “Then we realized we could kill two birds with one stone by creating stools that could also be crates to carry items like tools and our catalogs to Venice.” The final design consisted of two crates separable into four stools, which could then be ratchet-strapped together to form the multipurpose seating area.

Kraemer and Mansfield designed the catalog, a sleek, 8-inch-by-8-inch booklet bound in a textured, matte-black cover with two metal loops for hanging. Inside, images and accompanying text by Shibley, Delaney and Smith relate the history of the city and the school, provide information about each of the locations in the film, and contemplate the future of architecture education.

“We also helped curate the exhibition,” says Kraemer. “Our job was to develop the mood or feel of the space to complement the film.” They emblazoned the title of the film and an artist’s statement on the wall opposite the screen and artfully hung rows of the catalogs from nails, Mansfield explains, “so visitors could take a piece of the exhibit with them.”

A Venezia (“In Venice”)

“Venice is unlike any other city, and the Biennale is unlike any other event,” says Delaney. “All eyes are on it when it happens.”

During the days leading up to the Architecture Biennale, says Delaney, the fabrication team took all the ideas the team had for UB’s exhibition from hypothetical to actual—from conversations in Buffalo to installing the final project in Venice.

“It was exhilarating to watch everything we had ordered and shipped come together so elegantly,” says Faller. “The room was so dark and intimate once everything was set up. We were very proud.”

During the day, these three students were not having the typical tourist experience. They were in the Palazzo Bembo, interacting with Italian and other European partners involved in “Time Space Existence.” But at quitting time, they would leave the palazzo to wander and get lost in the streets and along the canals of Venice.

Wheeler describes Venice as a dreamlike experience. “It’s surreal,” he says. “With layers and layers of history, and canals and bridges and buildings intersecting. Venice is the perfect example of ‘Invisible Cities’ [a book by Italo Calvino about imaginary urban locations] realized.” Wheeler and the other students were also excited about exhibiting at the same venue as some of their architect heroes. “We are just a few doors down from Kengo Kuma and Peter Eisenman,” Wheeler enthuses. “It’s amazing that our work is being shown on the same level as people like that.”

Shibley flew in to meet Delaney and the team and to attend the exhibition’s soft opening. They watched as hundreds of people passed through UB’s darkened space and stopped to observe “See It Through Buffalo” as it played on a loop, the whir of turbine blades and the hum of busy students filling the room.

Faller’s favorite part of the Biennale was getting to see other people’s reaction to the film. “It was really cool to talk to people about the exhibition,” she says, mentioning a couple who watched the movie five times, and a man from Germany who used to live in Buffalo and stayed to discuss sites from the film with the team. “When we walked through the other spaces and mentioned we were from Buffalo, people immediately knew which space was ours and complimented it very much.”

At the U.S. Pavilion, UB faculty members conducted a workshop for Biennale attendees tied to the exhibition’s theme of citizenship. Photo: © Giorgio De Vecchi

Il Finale (“The Finale”)

In August, Delaney returned to Venice with 15 students and five faculty members for a study abroad program. The UB faculty engaged the students in tours and activities held throughout the city of Venice, delving into topics like preservation and adaptive reuse, as well as sustainable tourism. They even embarked on a “scavenger hunt” to determine the availability and cost of essential goods and services, as both have been impacted by Venice’s 60,000 daily visitors.

Clinical Associate Professor Kerry Traynor leading the UB study abroad group on a walking tour.Photo: Frank Kraemer

The program culminated with a workshop, also led by UB faculty, which was held at the U.S. Pavilion and available to anyone attending the Biennale. The workshop built on “See It Through Buffalo,” but also was tied to the Architecture Biennale’s theme of citizenship, and focused on the new role people in industrial cities, like Buffalo, must play in developing innovative solutions to address current social, environmental and economic challenges.

The exhibition itself is on display through Nov. 25, but by no means will that be the end of its run. Shibley mentions a roster of other events and projects that will stem from the film, including a series of web-based essays, articles, videos and illustrations highlighting each location in the documentary and the kind of work the school of architecture does within those spaces. A book is in the works, and there are plans to submit the film to festivals that celebrate documentary filmmaking. And, of course, “See It Through Buffalo” will be on exhibit in Buffalo, New York City and other locations around the country.

Wherever it goes from here, says Shibley, “Venice was a home run. The film touched people emotionally and even resonated with those who didn’t have an emotional attachment to our city, but had one to their own. They saw their cities in our film.”

The UB study abroad group on one of the oldest bridges in Venice. Photo: Gregory Delaney

Rebecca Rudell is a writer based in Buffalo.

A City of Contrasts

The 25-plus locations in the film include world-renowned masterpieces, UB campus buildings, and such structures as the former Niagara Machine and Tool Works, which UB is helping to transform into a manufacturing and workforce-training site on Buffalo’s East Side.

- Bethlehem Steel and Steel Winds

- Soldiers Circle

- New York Central Belt Line

- Darwin D. Martin House

- Boston Valley Terra Cotta

- One M&T Plaza

- Buffalo City Hall

- Commodore Perry Public Housing Project

- Reconstruction of GRoW Home

- Rigidized Metals

- Silo City

- “Front Yard Towers,” Burchfield Penney Art Center

- Guaranty Building